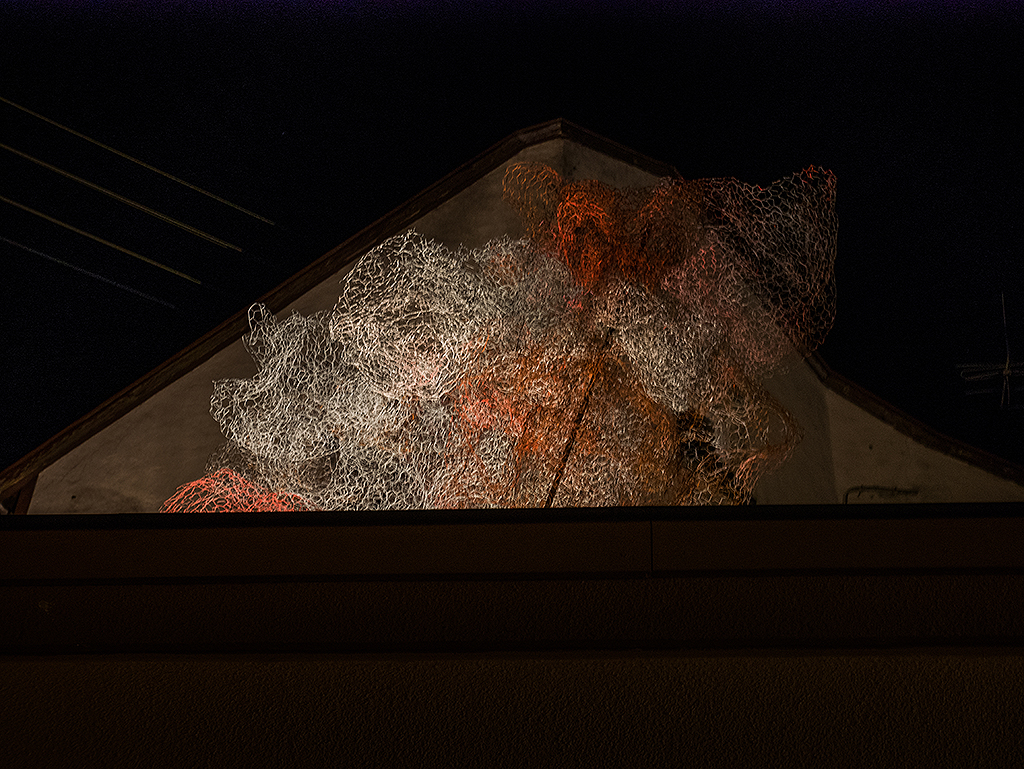

Four times four thin steel bars mark a square in the great outdoors, not too big, but not too small, the scale is geared in height and distance towards humans. The constructivist basis of these rods – they stand on galvanised plates of 1m edge length – carries a wild structure of thin wire mesh, formally as unimaginable as a cumulus cloud and with the trade term “chicken wire” almost poetically rewritten. The rods are glossy, the wire is bright, both have no inherent colour, but reflect back the light from the environment in all spectral appearances: in bright sunshine it is different from how it appears under a cloudy sky, under nocturnal artificial light it is different depending on the bulbs, depending on the background and also as a shadow on the floor or wall. But the appearance of the light always remains immaterial and the form remains open despite the firmly constructed ground. The sculpture won the 2015 TheRhinePrize and marks not only the greatest success of the artist Martine Seibert-Raken so far, but also reveals many characteristics of her work.

She started out with crafts and then finally arrived at fine art through design: Martine Seibert-Raken has been working for several years in the border triangle of these disciplines, with quite different emphases and in very diverse media. Her sculptural work reveals craftsmanship as well as design elegance, but also insists on artistic autonomy over almost any kind of commission. Sculptures by Martine Seibert-Raken combine wood and metal, but also light and iridescent plastics. Usually they stand alone, sometimes they hang as reliefs on the wall or as objects from the ceiling. Others, however, can be used as a table or a lamp and still retain their characteristics as a work of art. The most successful works by Martine Seibert-Raken are staged as installations in gardens, on rooftops or in urban areas. Like all good sculptures, the works must be viewed from all angles; you have to walk around them, approaching them sideways or from different perspectives in order to fully understand or enjoy them. For reliefs and paintings of course other rules for viewing them apply; they too are firmly anchored in the oeuvre of Martine Seibert-Raken.

The craft continues to be the basis of her artistic work, in the spirit of the sociologist Richard Sennett: The handling of material and tools is learned as implicit knowledge, i.e. by imitating masterly role models without linguistic distancing and reflection. 1 In all aspects of dealing with wood, the artist has the somnambulistic security that is only gained after a long time working with a material. She chooses the right wood for the right purpose, she knows the significance of the semi-finished product for the final shape and design, she knows how to differentiate all treatments of surface and internal structure and of course applies them without ever having to think about it – she just succeeds at everything. She had to first acquire this ability for other materials, from steel to canvas and the colours to be placed on them; Here, in every result, the already linguistically formed contemplation of one’s own actions is reflected. This applies in particular to painting, whose status in the society of fine art is not an easy one: The disagreements run through many works, including those by Martine Seibert-Raken. First and foremost, as Christof Breidenich once stated, there are disagreements about the medium that begin with the question of why painting or sculptural work should still be done, when computers can visualise the vast majority of things and almost everything can be found on the internet. 2

From the disagreements, contrasts arise: The designer places tables and benches on perforated metal plates, which also provide their support function diagonally, thus avoiding simple categorisation by looking at it. The contrast between a hollow shape – round cut-out of a square sheet – and a closed plate, which is needed for a functional table, comments on other contrasts: between round and angular, between heavy and light, between open and concealed. In addition, formal contrasts irritate behavioural expectations – those who have once watched with a smile, as people consider whether they may put a glass on a table by Martine Seibert-Raken or sit on one of her stools, experience these irritations as direct physical experiences. In the end, function always wins over the form, and then people even get comfortable surrounded by these objects. The hard metal stands on rough ground, crumbling paint blurs on the wall, soft wires carefully snake into the room, which is filled by visitors to the studio. All of Martine Seibert-Raken’s works ask for a precise placement, their traditional and deserved room.

The room requires colour, the designer knows this only too well. After many experiments, her objects are now characterised by material-specific colourfulness, be it in metal sculptures and designs or in painting, where light and dark earthy tones dominate and point to the basics of design: the ritual mixing of earth for application to objects and thus to their cultural elevation. So all in all, muted, earthy colours also dominate over the inorganic, chemical – a dark ox blood red, a dull indigo blue, these are the colours of the woods, which are adorned by chicken wire or other formless structures which as reliefs or sculptures move wildly from their base or the wall into the room into the room and there play with the light. The encounter with these reliefs is also a performance – more than with other sculptures of this kind –, because the forward and backward view avoids the delimitation of the pictorial space that has haunted the art of painting since the Second World War. Here, above all, the definition of the reason plays a major role, because this calibrates the view of the relationship between artwork and wall. 3 And this category is one of the few which leads from design to visual arts.

The décor is somewhat differently anchored in art, in principle more in the sense of the old meaning: the appropriate, also: the protection against change, imitation, generalisation and egalitarianism. 4 The décor also has a lot to do with surface, material and colour, which can be applied or a visible result of a working process. In metalworking, rust is often found in the function of the décor; It defines the time in which an object changes in terms of surface, colour and internal structures. But it also defines a time that is not that of man: Nobody can watch rust at work unless under special conditions to which Martine Seibert-Raken certainly does not subscribe. Nevertheless, as Thomas Raff has shown, processes of oxidation in general and on metal in particular have been an important element in artistic formulations since the beginning of sculptural design. 5 Also the chicken wire is not protected against rust and will someday look different than in the pictures of the award-winning installation.

Broadly speaking, with the matrix of form | Material | Colour | Décor already outlined the repertoire of artist Martine Seibert-Raken; No virtuosity of the brush stroke, no orgy of sandpaper and steel polishing wool, no meticulous preliminary design, and no apparatus of dozens of helpers are needed to realise the objects. From the scale as well as for production, the arms and legs of the artist are sufficient for her to determine the size; depending on its weight and volume, a lifting tool may occasionally be used, but even then, the framework of action is manageable – in sculpturing this by no means an obvious prerequisite. However, it is this human scale that makes art and the design of Martine Seibert-Raken directly accessible, no matter where and how her work is staged. Once you have experienced this in the midst of her works, you notice the congruence of person and work, and you will feel directly suspended in the ambience of her work. The design of Martine Seibert-Raken can be translocated, steps back in daily use, becomes a natural backdrop of life. On the other hand, the art of this artist wants to be re-experienced every day, as well as being entitled to repeated views and arguments. Both are based on the same craft, but only in seeing, thinking, recognizing, re-thinking and especially in the conversation about the work, the difference between design and art can be experienced – and it is still the same person who created this.

Dr. Rolf Sachsse

1 Richard Sennett, Das Handwerk, Berlin 2008, S.44-79.

2 Christof Breidenich, Malerei – die Ruhe während des Bildersturms, Diss.phil. Wuppertal 1999.

3 Gottfried Boehm, Matteo Burioni (Hg.), Der Grund. Das Feld des Sichtbaren, Paderborn 2012.

4 Andreas Brandolini, Carsten Feil, Yann Grienberger, Bernard Petry (Hg.), Ausst.Kat. Decor.um, Relecture contemporaine des techniques traditionelles de décor du verre, Meisenthal 2009.

5 Thomas Raff, Die Sprache der Materialien. Anleitung zu einer Ikonologie der Werkstoffe, München 1994.